Universal design for learning (UDL) is a learning design approach that works to accommodate the needs and abilities of all learners and attempts to minimise unnecessary barriers to the learning process. In this post, Dr Natasha Todorov, who is the unit convenor for a (very) large first year psychology unit outlines how she applied UDL principles to reorganise the iLearn unit to meet the needs of a growing neurodiverse student cohort.

The context for change (the Why)

In many ways PSY1102: Introduction to Psychology II is a typical Macquarie University first year unit. We teach foundation, or introductory concepts to a broad cohort of students with three different tutorial modes: flipped on-campus in-person, flipped on-campus zoom online, and via Open Universities Australia (OUA), which is completely online delivery.

One way we may be atypical is that this unit has had an enrolment of 2,500 students per year, over the last three years. We are a Very Large Unit. It is unsurprising that with this many students enrolled we have a hugely diverse cohort. The principles surrounding equity, diversity, and inclusion often refer to assessment and design strategies which are best utilised by units with much smaller enrolments (e.g. design or assessments which have been used successfully with Decently Large Units with enrolments of around 500-1000 students, or Tall-to-Venti Units < 500 students). This article will discuss some applications of Universal Design Principles which I applied to a Very Large Unit. They have the advantage of being low tech, relatively simple and easily replicable across units in a course or Faculty.

The redesign of PSY1102 was spurred by the increasing enrolment of students who identified as being neurodiverse (see box). Many in this cohort had difficulties coping with the rule structure of the university and the presentation of complex information on the unit iLearn page.

Neurodiversity is an umbrella term that encapsulates a variety of conditions e.g. acalculia, dyslexia, ADHD, Autism Spectrun Disorder (Shah et.al., 2022). One aspect of cognitive functioning that these conditions have in common is an apparent difficulty in executive processing abilities eg self-control and selective attention, working memory, and cognitive flexibility (Diamond, 2013). That is, students who are neurodiverse and have difficulty with executive processing, may have difficulties in any combination of the following:

- the ability to plan

- the ability to organise

- memory difficulties

- the ability to set appropriate goals

- the ability to shift from one task to another

- the ability to appropriately self-reflect on performance

Research has indicated that factors such as available cognitive load in university students with and without learning disabilities, affect their academic performance (Bishara, 2021). I set up PSY1102 to minimise these barriers to learning by changing the way we present information to students and by encouraging them to learn and practice academic skills that might assist in lowering the cognitive load associated with the unit.

The What

Universal design for learning (UDL) is a teaching approach that provides a scaffold for educators attempting to eliminate unnecessary barriers to learning.

Using these Guidelines, I applied UDL principles to our iLearn unit page design, using six strategies to minimise cognitive load.

1. Chunking and differentiating information for easier processing (see UDL Checkpoint 3.3)

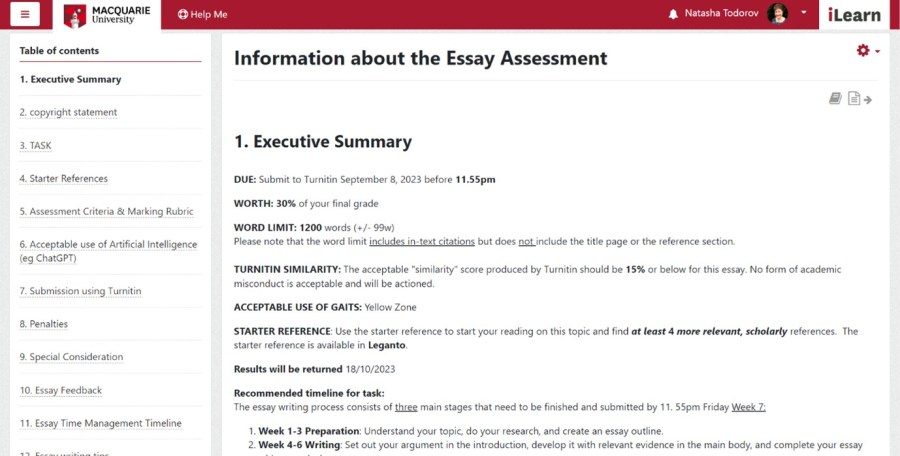

Rather than providing information in long documents, information is chunked into book chapters. The illustration shows you our “Essay Information Booklet” as an example. This booklet is printable and downloadable and contains all the information required to write the essay (plus essay writing tips!). Each chapter is short and is devoted to one point. We follow up the essay writing tips with short practical writing exercises in the early tutorials of the semester.

Importantly, each book starts with a summary page listing all the important information, preventing students getting buried in detail, thus differentiating the level of information provided to students. If a student cannot cope with the detail on a given day they can find the most frequently asked information on the summary page. This takes a considerable cognitive load off, when necessary.

Bonus tip for unit convenors: When students ask a question on the discussion board or in an email you can direct them to the answer on the iLearn page by cutting and pasting the web link to that page or by screenshotting the page and inserting it into your answer. Links are a handy efficiency and often direct students to other useful pages they may not have found by themselves.

2. Explicitly teaching organisation and time management (see UDL Checkpoints 6.2; 7.3)

We provide a recommended timeline for success, and we explicitly recommend using MyLearn to help keep on track.

The PSY1102 timetable is illustrated for you. It provides a visual representation of a study plan we enact for the students throughout the semester. Students can see which week readings become active, in which week assignments are due, and a plan that allows them enough time to get each assessment finished before the next is due. There is clearly ample time for every assessment.

We provide popular weekly to-do lists with tickable boxes (see illustration) to explicitly teach the plan we have envisioned above. Students have told us the tickable boxes are particularly important as they are concrete cues that a task has been completed that week which lifts a burden on memory. Weekly Announcements provide a reminder newsletter that integrates the units many parts for the students and provides a scaffold describing what they are learning and how it all fits together.

Students are provided with a 4-step schema to tackle each of the seven topics we teach in this unit. This shows students how all the learning activities work together to promote learning. The schema is illustrated below.

Students are encouraged to listen to the lectures using the learning objectives as their guide, participate in tutorials (which are linked to the lecture materials), read their text, and then attempt the Ten-Minute Topic Test (a bi-weekly formative assessment to keep students on top of their lecture material). Students are encouraged to be ACTIVE learners (e.g., Lombardi et. al, 2021) in each step and to LEARN AS THEY GO, not leave it all to the last minute (ie to manage their time wisely).

3. Publishing learning objectives for lectures and tutorials (see UDL Checkpoint 3.2)

This is very important in helping students focus attention on the lecture structure and learn to filter out the main points in the stream of words. First year students are only just learning how to take lecture notes, so this is a good way to help all our cohort develop an important tertiary level skill.

This was a well-received initiative and a clear path to success for all students, not just the neurodiverse cohort. Learning Objectives were also published for each tutorial – students really appreciated having Learning Objectives!

4. Explaining the rules, not just listing them (see UDL Checkpoint 7.2)

Students are less likely to get upset when they know WHY we have seemingly random administrative rules in place. For example, the need to append a special consideration email to an essay seemed one task too many to a student with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) until it was explained that, because of the size of the cohort, it was not feasible for us to do that individually for each special consideration. We explained the rule was there to stop anyone falling between the cracks. Once explained the student was less upset and happier to comply.

5. Providing students a “3 Steps to Success at Uni” plan

Providing students with a Steps To Success plan emphasises important generic learning skills: building connections, self reflection, and actively seeking assistance (see illustration). It was emphasised that this (as well as the other skills they were learning eg time management) were skills that could be applied across all their units at Macquarie University and into life beyond tertiary education. The information for this (as with many aspects of this unit) is supplied in both written handouts and short videos which corresponds to the UDL principle of providing Multiple Means of Representation (UDL Checkpoint 2.5).

Step 1 – Build Connections:

- We encourage our students to attend and participate in their tutorials, get to know their tutor, and fellow students. We encourage students to interact with the unit material, ask questions, participate in group activities, and apply what they’ve learned to real life case studies.

- We suggest that Building Connections with fellow students and staff is an important part of being an active learner as well as building connections between the various aspects of the unit and encourage this as much as possible.

- The main tool we use to teach the concept of “Building Connections” is “active learning”. Active Learning is explicitly taught. We provide examples of what “active learning” looks like in our unit (in a lecture situation, in a tutorial, on a discussion board) and reminders to engage this way during the semester.

Bonus tip: PASS is an excellent forum for all these activities – for revision and for building connections. It is often the only “live” encounter OUA students receive, and in past years our OUA students have taken up PASS sessions enthusiastically.

Step 2 – Self-Reflection:

- Academic self-reflection is a useful generic skill for students (Lew et. al., 2011). We encourage our first-year students to think realistically about their academic progress from the start of the semester and provide resources and encouragement to learn and apply this skill.

- We ask students to think about how they are going with their assessments across all their units. Have they received any grades back, and if so, are they what were expected? What were the comments like? We encourage students to use a one-minute self-reflection after each lecture to focus on the three main take-away points that they learned and the one issue that they need to follow up on if they are still confused. The former list can be kept to assist with lecture revision later, the latter can be used to follow up at tutorial “Question Time” or a Discussion Board post directed to the lecturer.

If a student feels they are not doing as well as expected there are many avenues for support. Students can self-refer, or a staff member can refer them to a Macquarie-based program – see below.

Step 3 – Finding Assistance:

- Students who have difficulty coping with high levels of cognitive load are less likely to look for help if it is difficult to find (e.g., Dong et. al., 2020). It is one step too much.

- In order to assist students in this situation I have gathered as many resources as I have been able to find and put them in one booklet on my unit iLearn page so that students in need of assistance can browse and decide what might suit them best. The Student Support Hub (see below) is in its own, highly visible tab and designed to make finding assistance easier.

6. Creating a unit Student Support Hub (UDL Checkpoint 8.3).

The Student Support Hub includes Technical, Academic, Personal and Crisis support.

Students who suffer anxiety, panic, or trauma are often unable to search for information themselves so having all that information in one place reduces the cognitive load when stressed.

The resources in the Student Support Hub vary in their mode – they include videos, texts, links to phone services, chat lines, email addresses, and web pages. They cater to diverse groups both within Australia and cater for students who are based overseas. Resources included span both Macquarie University based services and selected non-university resources.

Results of a small trial in 2022 indicate that organisation of information appears to have been helpful for all our students. The average grades for OUA students, who rely entirely on the presentation of material on our iLearn page, were particularly positively impacted in 2022. This has been very encouraging and suggests the potential impact that making these types of changes to the accessibility of information can make to learning outcomes across the board.

Most importantly, students have indicated that the changes are working for them:

This unit was the most organised so far. It helped keep me on track and on top of my learning.

I appreciate how she checked in on us and the resources she provided to support our mental health.

Well structured lectures, well structured tutes, plentiful resources for helping.

I felt supported and accommodated despite it being a pandemic”

References

Adams, R.A. & Blair, E. (2019) Impact of Time Management Behaviours on Undergraduate Engineering Students’ Performance. SAGE Open, 9 (1) doi.org/10.1177/2158244018824506

ADCET (2023) Universal Design for Learning. https://www.adcet.edu.au/inclusive-teaching/universal-design-for-learning. Accessed 11 July 2023

Bishara, S. (2021) Psychological availability, mindfulness, and cognitive load in college students with and without learning disabilities. Cogent Education, 8 (1) doi : 10.1080/2331186X.2021.1929038

CAST (2018). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 2.2

Diamond, A. (2013). Executive Functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135-168 doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750

Dong A, Jong MS, King RB. (2020) How Does Prior Knowledge Influence Learning Engagement? The Mediating Roles of Cognitive Load and Help-Seeking. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 591203. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.591203.

Lew MD, Schmidt HG. (2011) Self-reflection and academic performance: Is there a relationship? Advances in Health Sciences Education : Theory & Practice, 16(4), 529-45. doi: 10.1007/s10459-011-9298-z.

Lombardi, D., Shipley, T. F., Bailey, J. M., Bretones, P. S., Prather, E. E., Ballen, C. J., Knight, J. K., Smith, M. K., Stowe, R. L., Cooper, M. M., Prince, M., Atit, K., Uttal, D. H., LaDue, N. D., McNeal, P. M., Ryker, K., St. John, K., van der Hoeven Kraft, K. J., & Docktor, J. L. (2021). The Curious Construct of Active Learning. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 22(1), 8–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100620973974

Shah, P., Boilson, M., Rutherford, M., Prior, S., Johnston, L., Maciver, D., & Forsyth, K. (2022). Neurodevelopmental disorders and neurodiversity: Definition of terms from Scotland’s National Autism Implementation Team. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 221(3), 577-579. doi:10.1192/bjp.2022.43

Acknowledgments: Banner Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay UDL graphic -Giulia Forsyth via Flickr (Creative Commons). Post edited and reviewed by Karina Luzia.

Share this: